......

...... ......

...... ......

......

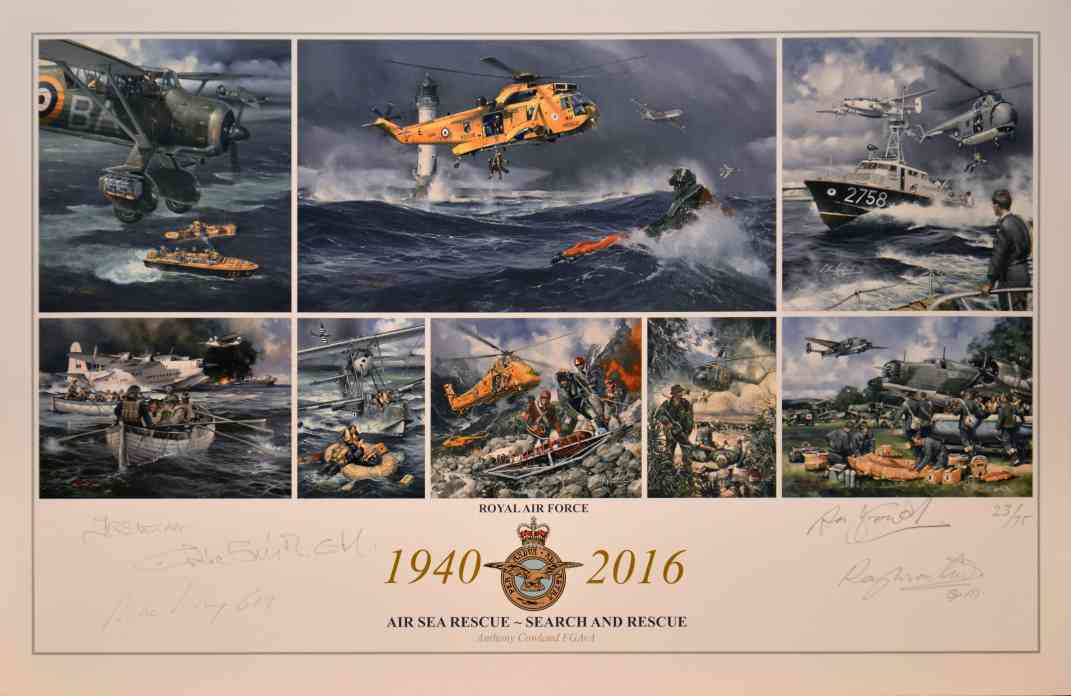

RAF HELICOPTERS IN SEARCH AND RESCUE

......

...... ......

...... ......

......

EARLY BEGINNINGS

Helicopter Search and Rescue had its dramatic birth in the Far East theatre of operations during the Second World War. Three of General Orde Wingate's Chindits were being evacuated by a light L-1, single-engined fixed-wing aircraft when the aircraft suffered an engine failure and the pilot was forced to land in a paddy field in Japanese held territory. Among the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) units supporting the Chindits was an experimental flight of three Sikorsky R-4 Helicopters which had been sent to the theatre for battlefield evaluation. Lieutenant Carter Harman of the 1st Airborne Commando, USAAF set off from a rear base at Lala Ghat near the eastern Indian frontier on a 600-mile transit flight, over mountains rising to 5000 ft, to the battle zone. He lifted out the four survivors, two at a time. Little more is known of this epic journey in a fragile, experimental aircraft; however many other deeds were completed by the 1st Airborne Commando USAAF proving the value of the helicopter as a rescue vehicle. The title Air Sea Rescue changed to Search and Rescue as the capability to search for survivors was enhanced between 1945 and 1950.

In the years just after World War Two into the early 1950s very little was thought about helicopters within the RAF. The RAF was mostly concerned with the operation of the relatively new jet aircraft, the Venom, Vampire and Meteor, which, because of their difficulty of operation and unsophisticated technology, saw a significant number of aircraft losses. Unfortunately these also led to loss of aircrew, whose operating area was no longer restricted to the English Channel area where current Air Sea Rescue forces existed. It soon became clear that an UK-wide SAR service was needed. Moreover, agreement was already in place, from 1947, for the Air Ministry to assume responsibility for operation and administration of all search and rescue arrangements for both military and civil aviation.

In the meantime the Royal Navy was evaluating the helicopter as a possible successor to the Sea Otter and as a much more economical replacement for the escort destroyer, which always followed an aircraft carrier during flying operations in case of accident. The Royal Navy was sufficiently confident to order 60 "Dragonfly" helicopters made by Westland Helicopters Ltd, a development of the Sikorsky R-5. The first of these were delivered in 1947 to 705 Squadron, HMS Siskin, Naval Air Base, Gosport, Hampshire. On the night of 31 January / 1 February 1953 extraordinary weather conditions in north west Europe resulted in devastating floods in Holland and along the east coast of England. The full operational strength of 705 Squadron was deployed to Holland to assist with the rescue of people from rooftops, flooded fields, boats and dykes and to ferry medical personnel, supplies and food to remote areas. Approximately 800 people were lifted to safety.

It was during this operation that the, now standard, NATO Rescue Strop was invented by an officer of the Royal Netherlands' Navy. A claim for this invention has been put forward on behalf of the Royal Navy, which says that it was invented by an Aircrewman in HMS Theseus in the early 1950s and was used in the rescue of a pilot from a ditched Sea Fury on 4 August 1953. Nevertheless, the strop was developed by the Royal Navy at Gosport and has remained a standard method of lifting survivors ever since. New survivor handling considerations may see the introduction of a new strop in the near future. Prior to this time the winch hook was used which fastened on to a fitting on the aircrew "Mae West" life jacket.

The RAF's interest in Maritime helicopters at this time was centred in the Air/Sea Warfare Development Unit that had evaluated the Hoverfly 1 and 2. However it discarded them when it became apparent that they had no useful function in operational maritime rescue or anti-submarine operations. It was not until the Air Sea Warfare Development Unit moved to RAF St Mawgan in December 1951 and the arrival of the new Sycamore helicopter in February 1952 that the development of maritime helicopter operations was given the impetus that led to the formation of the Helicopter SAR Force that we know today. SAR equipment at the end of 1952 comprised a rope ladder and safety lines. During a deployment of a Sycamore to RAF Linton-on-Ouse, for daily SAR cover at Patrington for Exercise Ardent, it became evident that a winch was essential for sea rescue operations. The first winch arrived in 1953 and was allocated to the newly forming 275 Squadron.

From April 1950 and until 1953 the RAF's operational helicopter force comprised the Far East Air Force Casualty Evacuation Flight. This was formed at Seletar, Singapore to provide casualty evacuation for troops engaged in the remote jungle areas of Malaya during the Malayan Emergency. The unit was initially equipped with the Dragonfly but later competed, along with other newly forming helicopter units in the Middle East, with 275 Squadron for allocation of the Sycamore. The Casualty Evacuation Unit was a resounding success from the beginning and operated throughout Malaya for 20 months before losing its first aircraft to the far from neutral jungle. By 1953 it had expanded to form 194 Squadron.

In October 1952, the global strategy envisaged the formation of two SAR squadrons of 16 helicopters each, one in Fighter Command equipped with Dragonflys and one in Coastal Command equipped with Whirlwinds. Almost immediately, a 12% cut in expenditure caused these figures to be halved while the Sycamore was to be substituted for the Dragonfly in Fighter Command. The Sycamore was deemed sufficiently powerful for the rescue of fighter aircrew; however, the more powerful Whirlwind was needed for the heavy-aircraft crews (five men at 100nm range). It took about three years (1953 - 1956) to build up the force to the point where the nine planned deployed Flights were able to offer standby over the whole of the East and South coasts, Wales and part of the Irish Sea. The Whirlwind 2s and the Sycamores had an effective maximum radius of action of 50nm. During the first two years the embryonic 275 Squadron, with only a few Sycamores, spent much of its time moving from one detached location to another in an attempt to provide SAR cover where fighter exercises were taking place. The end of 1956 saw the pattern of permanently detached Flights established which remains today; only their number and location has changed since with the advent of longer-range helicopters.

275 Squadron was re-formed in 13 Group of Fighter Command, with Sycamores at RAF Linton-on-Ouse on 13 April 1953 with 3 pilots (including the Squadron Commander - Flight Lieutenant D C Kearns) and three crewmen/ navigators. The second Sycamore, its original complement, arrived on 16 April 1953 and SAR standby commenced on 20 April with a 10 minute readiness during normal working hours and one hour otherwise, restricted to daylight operations only. The first operational sortie was carried out on18 April 1953 with an abortive search for a reported ditching. With its two Mk 13 Sycamores, the Squadron responded to a series of demands for operational SAR standby tasks at various places along the East Coast. These simulated the latter pattern of fixed detachments, by appearing for a few hours or days at a time, for example at Patrington, Strubby, Sutton-on-Hull, North Weald, Coltishall, Boulmer, Acklington, Bridlington Bay, Manston, Marham, Thornaby, Horsham St Faith and Bampton.

In the early and mid-1950s there was a higher ratio of aircraft crashes on land as opposed to water. A large number of Venoms, Vampires and Meteors were flying at that time and crashes and bale-outs were comparatively frequent. The first rscue carried out by 275 Squadron was of a Venom pilot recovered from Boulmer (disused) to Acklington in August 1953.

In 1954 the Squadron acquired an Auster Mk V, two Hiller 360 helicopters as well as 2 Chipmunks, 2 Ansons and an Oxford. The Mk 13 Sycamores were reserved for new crew training (four of the seven crews being held in readiness for overseas duty in Middle East Air Force or Far East Air Force). In August 1954 Sycamores flew only 3 sorties against 21 by Hillers, 13 by Ansons, 15 by Auster, 9 by Chipmunk, and 3 by Oxford. The Hillers were used for land rescue and the Ansons for sea searches. No sea rescue was possible for most of the last part of 1954, although some rudimentary standby was maintained as it had since the Squadron reformed, perhaps prematurely, in April 1953. The Squadron HQ and basic standby moved to Thornaby-on-Tees in November 1954. 1955 saw the build up of Sycamore Mk 14 on the Squadron and by May both Hillers had been returned to the Royal Navy. The Squadron started to assume the operational helicopter posture that was to last for many years. The first permanent, detached flights were formed at North Coates in February, Leuchars in June and Horsham St Faith in September with the Squadron Headquarters co-located with a Flight at Thornaby. During 1956 the Squadron's strength of aircraft and crews was depleted to seven ac, against an establishment of sixteen, by the build up of Sycamores in Cyprus. This situation began to improve by the end of the year and in June and July 1957 two new Flights were established at Chivenor and Aldergrove. The Squadron Headquarters was moved to Leconfield in September and was joined by the Flight from North Coates; in October the Flight moved from Thornaby to Acklington. By the end of the 1957 the full complement of six flights was established, with a total strength of 15 Sycamores, at Leuchars, Acklington, Leconfield, Coltishall, Chivenor and Aldergrove. These provided SAR cover for much of the East and West coasts. During this period the Squadron's helicopters were ordered to be painted bright yellow with the word "Rescue" on the sides; giving rise to the familiar colour scheme used on RAF Rescue Helicopters in the UK from that time to the present.

In the absence of an Operational Training Unit, SAR training was carried out on the Squadron, not only for its own crews but also for those Sycamore units being formed in Sylt, Aden and Cyprus. Initial pilot training was carried out on the Sycamore at the Central Flying School (CFS) and in April 1956 a Sycamore Qualified Helicopter Instructor (QHI) was produced to fill the Squadron Training Officer post. Prior to then pilots were generally ignorant of many aspects of helicopter flight including engine-off landings; this was rectified just in time for the Squadron's first engine failure over the sea which occurred without injury to the crew. The crew of the Sycamore comprised a pilot and navigator. The initial intention was for the navigator to act as winch-operator and for a strop to be lowered to the survivor. However, this was clearly unsatisfactory from the outset, as it required the survivor not only to be sufficiently fit to place the strop on himself but also sufficiently competent. The next idea was to employ the "Sproule Net", designed by Lt Cdr John Sproule RN, in which the survivor could be scooped out of the water without taking an active part himself. The Sproule Net was designed for use with the Dragonfly and although some satisfactory results were obtained with the Sycamore there was a problem with the position of the engine exhaust, which tended to burn the net and sometimes the survivor as well. If not delivered accurately the structure of the net could strike the survivor with disastrous results; furthermore, the net could not be used on land. Although not adopted for the recovery of survivors, the Sproule net continued to be employed in training for the recovery of bodies from the water into the late 1970s.

By July 1955, the conclusion was reached that a winchman was required to be lowered on the winch cable to effect the rescue of the survivor. With only a two-man crew the navigator was lowered on the winch cable with the pilot operating the winch controls from his cyclic stick. Communication between the two was maintained by a long inter-com lead. The winchman continued to give patter to the pilot to place himself with the survivor; this appeared to be workable until the winchman entered the water when his instructions suddenly ceased as the water caused the system to short-circuit. To provide the pilot with a view of the winchman on the end of the wire below the aircraft, a polished convex hubcap, from a Hillman staff car, was placed on the winch arm. This could be seen with the addition of an ordinary rear-view mirror mounted in front of the cockpit. In December 1955 during a practice lift, a Sycamore struck the Bell Rock Lighthouse and both pilot and crewman were killed. It was not possible to recover the bodies by helicopter as the Sproule Net could not be used on land and there were problems with the long inter-com lead, which prevented a double lift being used. The only satisfactory long term solution, notwithstanding the loss of range and cabin space, was now seen to be provided by adding a third crewmember, a winch operator, to operate the winch with the winchman on the end of the winch cable. By January 1956 this solution was reluctantly beginning to be accepted for the Sycamore squadron; it having been adopted at the outset for the Whirlwinds of 22 Squadron with their much larger cabin area. Nevertheless, the carriage of a third crewmember was still regarded as such a disadvantage that experiments with the long inter-com lead and mirrors continued until August 1957 when crewmen started to be trained purely as winch-operators for 275 Squadron, increasing the crew complement to pilot, winch-operator and winchman.

The Neil Robertson stretcher became the standard stretcher used for lifting immobilised casualties from 1956 onwards. Navigational assistance was provided by a VHF fixer service given by the Sector Control operated primarily for the fighter force until the introduction of Decca after 1958. Homing equipment was first fitted in 1954, initially to the Squadron Anson and later to the Sycamores and this provided homing to aircrew survivors. By April 1958 all 275 Squadron crews were fully trained for night and instrument flying and practised in engine off landings and by May they were officially cleared for night transit flying and rescue sorties over land.

The basic rescue equipment used by the Winchman has changed very little since the early Whirlwind days. The Winchman had an Immersion Suit, a Bosun's Chair and Quick Release Fastener, a NATO Strop and a Grabbit Hook. The Neil Robertson Stretcher was the standard stretcher used. A First Aid Kit was available. Improvements have been made over the years with developments in aircraft and equipment technology. A greater variety of equipment is also now carried, nevertheless; the basic equipment remains largely the same.

In May 1958 Coastal Command assumed responsibility for all Search and Rescue and 275 Squadron was transferred to 18 Group. In November 275 Squadron's Chivenor Flight was handed over to 22 Squadron and in April 1959 the Aldergrove SAR Flight was withdrawn to be replaced by 118 Squadron with Sycamores. In early 1959 Whirlwind Mk 2s began to replace the 275 Squadron Sycamores and the Squadron operated a mixture of Whirlwinds and Sycamores until December. In September 1959 275 Squadron was renamed 228 Squadron. The last Sycamore SAR operation, a medevac from Colonsay to Oban, was completed during May 1960 and, with 11 Whirlwinds established, SAR operations continued unabated with 228 Squadron Flights at Leuchars, Acklington, Leconfield (co-located with the Squadron Headquarters), and Coltishall.

There was a comparatively large number of land rescues during this period as the RAF still had many fighter aircraft exercising in the northern and eastern areas of the country. For example, in July 1958 the Squadron was called out for 24 incidents involving an Auster, a Provost, a United States Air Force B66 bale-out, a Sea Venom short of fuel and a parachute sighting as well as a submarine search, a range incident, several medevacs and bathers in difficulty.

In October 1962 the jet turbine-engined Whirlwind 10s started to replace their piston-engined predecessors (Mk 2 and 4) with 228 Squadron; in November a few were on SAR standby and by December the changeover was complete. On 1 September 1964, 228 Squadron was renumbered 202 Squadron, having been selected to carry that title after 202 (Hastings) Squadron was disbanded after its meteorological reconnaissance role had ended. 202 Squadron maintained its headquarters at Leconfield with Flights at Leuchars, Acklington, Leconfield and Coltishall. The transition from 275 to 228 and finally to 202 Squadron appears to have progressed smoothly, building on the expertise and experience of its predecessor.

22 Squadron was reformed as a SAR helicopter squadron at Thorney Island within 19 Group on 15 February 1955. It was tasked with sea rescue and land search and rescue over a range of 60nm. It had an initial establishment of eight Whirlwind Mk 2s and was planned to operate from four detached Flights to provide SAR cover over the South and South East Coasts and Wales. One Flight was located with the Squadron headquarters along with operational training facilities and second line servicing. The crew comprised a pilot, navigator and crewman. A specific crewman trade did not exist at this time. In Malaya this deficiency had been made up by using technical ground tradesman to assist with servicing away from base. This aspect was not so pressing for 22 Squadron and in July 1955 three administrative orderlies were allotted for crewman duties, receiving an additional one shilling and six pence per day for the privilege. AC2 Raymond Martin was posted to Thorney Island from where on the 5 Jun 1956 he was involved in a rescue that earned him the George Medal, the first of five to be awarded to SAR Helicopter Winchmen. It is interesting to note that the technical emphasis continued in Support Helicopters with the introduction of the Loadmaster trade. Crewmen in Support Helicopter were required to gain a significantly high level of technical knowledge of their aircraft whereas those posted to SAR helicopters needed only a general understanding of technical subjects.

The very next month there were well-founded rumours of imminent disbandment as no aircraft had arrived and all postings to the Squadron had been suspended. However, two Sycamores were allotted from the Air Sea Warfare Development Unit to enable the Squadron to continue forming. By May the Squadron had two Sycamores and an Avro Anson and was looking and functioning very much like a Flight of its predecessor, 275 Squadron, in its early days. Four Whirlwinds arrived during June and the first two Flights were formed at Thorney Island and Martlesham Heath. The third Flight was formed at Valley in September to provide cover for the West Coast and became operational the following month; it was also the first SAR Flight to have a Navigator as Flight Commander. A Sycamore had to be borrowed once more from the Air Sea Warfare Development Unit when two Whirlwinds were lost from the Squadron. One was sent to the Far East Air Force, the second was found to be suffering from corrosion. Corrosion was to remain a significant problem for the magnesium alloy built helicopters used in the maritime environment for many years to come; indeed the later Wessex HC2s were re-skinned with aluminium to reduce the problem.

By April 1956 22 Squadron was operational with all four Flights, the last being formed at St Mawgan to where the Squadron HQ also moved in June. The Flight at Martlesham Heath moved to Felixstowe in April. The Flights at Thorney Island, St Mawgan and Felixstowe were controlled by the Southern Rescue Co-ordination Centre (SRCC) at Plymouth. The Flight at Valley was in the geographical area covered by the Northern RCC at Pitreavie Castle, Edinburgh. In October 1956 a Flight was formed at St Mawgan destined for SAR cover and communications flying in Christmas Island for the British nuclear tests (Op Grapple). The "Grapple Flight" departed on 30 January 1957 and arrived in Christmas Island on 4 March to commence SAR standby on 6 March. Characteristically the helicopter facility became indispensable and consequently grew, mainly with communications flying, over nine months to the extent that 217 Squadron was formed in January 1958 to carry out the task. The residual Grapple Flight personnel returned to be re-absorbed into the main element of 22 Squadron. Among the 22 Squadron personnel detached to Christmas Island was AC Raymond Martin GM; on his return to UK he was posted to St Mawgan to be a "Staff" winchman on the Training Flight until his discharge from National Service.

In November 1958 A Flight 22 Squadron moved from St Mawgan to replace the Flight of 275 Squadron at Chivenor as part of a geographical rationalisation of responsibility. The Headquarters Flight formed at St Mawgan mainly for the training of crews but also having a SAR standby facility. The Training Flight acquired the status of an Operational Training Unit in July 1959 and continued to maintain a limited operational capability. It also provided operational training for new pilots arriving from the CFS Helicopter (CFS(H)) Training School and Navigators/Signallers arriving directly. In December 1959 the Flight at Thorney Island had to be withdrawn, much against the wishes of the local public, temporarily leaving SAR cover on the South Coast on an "ad-hoc" basis by the Royal Navy. This situation was rectified by the move of the Felixstowe Flight to Tangmere in May 1961 and the replacement of the Thorney Island Flight by the re-formation of the fourth Flight at Manston in July 1961. The Operational Training Unit was now in a position also to provide standardisation for 228 Squadron, the whole SAR force by then being equipped with Whirlwind Mk 2s. Conversion to the Whirlwind Mk 10 started in May 1962 and was completed by September of that year. One of the early Whirlwind Mk 10 rescues resulted in the second award of a George Medal to a Winchman. Sgt Eric Smith volunteered to be lowered to the stricken French fishing vessel, "Jeanne Gougy", to rescue two trawlermen from inside the wheelhouse, which was continually being submerged by breaking waves.

By the late 1950s the public placed great value on "their" rescue helicopters and any move by the Royal Air Force to close or move the SAR helicopter flights was resisted with great vigour. The drama that ensued following the closure of the Thorney Island Flight in December 1959 had shown that the public outcry and lobbying by local officials could force modifications to the RAF's deployment plans however well justified by the RAF. Thus in May 1961 when the Flight at Felixstowe was due to be deployed to Manston it was diverted instead to Tangmere, close to Thorney Island. A further flight then had to be established at Manston to close the gap in SAR cover. An additional motivation for this change existed because of Air Staff annoyance that, in holiday weeks, the Solent and South Coast were treated to frequent views of rescue helicopters bearing the words "Royal Navy" in large letters. These helicopters were equipped for anti-submarine warfare and tended to be operated during normal working hours, and were therefore not available to hold the regular seven-days a week SAR service that the RAF was obliged to maintain. In 1964, due to the closure of Tangmere, the Flight returned to Thorney Island, thus returning the South Coast helicopter flight to its former home from where its withdrawal caused so much trouble in 1959/60. In March 1969 history was to repeat itself when the Manston Flight was selected for closure. The aircraft and crews being required to deploy to reform, briefly, 1564 Flight at El Adem following the crash of an Argosy in Libya. A reduction in fighter aircraft activity in the South, and therefore SAR requirement, coupled with a shortage of crews, lead to the judgement that the Manston area could be covered by Coltishall in the North and East and Thorney Island to the South and West. The literary and vocal outcry was sufficiently strong to cause the Department of Trade to contract Bristow Helicopters Ltd to provide an air-sea rescue service, directly under the control of the Coastguard, operating Whirlwind Series 3 helicopters (the civilian equivalent of the RAF's Mk 10s).

During its three-year tenure from 1 June 1971 to 30 September 1974 668 rescues sorties were flown and 108 lives preserved. In 1972 a crew from Manston was awarded the "Wreck Shield" by the department of Trade and Industry for the "Most Meritorious Rescue in 1972". The crew was: Pilot Lee Smith (who was also the pilot during the Sea Gem rescue for which Sgt John Reeson was awarded the George Medal), Navigator Peter Redshore and Winchman Pat Ingoldsby.

A less controversial move was of 228 Squadron's Flight from Horsham St Faith to Coltishall in April 1963.

The arrival of the Whirlwind Mk 10 in the latter part of 1962 saw a significant increase in the capability of SAR Helicopters. They continued to be operated as before; but with up to a 30% increase in fuel/pay load, the aircraft had a greatly enhanced range and was able to respond more successfully to a wider range of tasks. As a result the public were becoming progressively more aware of and reliant upon the rescue service the helicopters provided.

It needs to be emphasised that that an individual call-out to an incident did not necessarily infer the rescue of an individual or indeed the number of individuals rescued. For example, in 1966 22 Squadron recorded 34 aviation incidents resulting in 14 persons being rescued, 69 air ambulance/casualty evacuations, 70 swimming incidents resulting in the rescue of 16 persons, 252 small boat/yacht incidents involving 137 rescues, 59 operations on behalf of persons marooned on cliffs resulting in 61 rescues, 56 operations with 42 rescues described as miscellaneous and 27 false alarms.

The four flights of 202 Squadron covering the East Coast of Britain had generally longer ranges to fly than those of 22 Squadron which, being deployed in the more highly populated South, consequently dealt with a higher rate of incidents. Whereas 14% of 22 Squadron's flying time was classed as operational the corresponding figure for 202 Squadron was 10%. These figures differed little year by year from 1964 to 1969, as did the total annual flying rate, which averaged 3877 hours for 22 Squadron and 3458 for 202 Squadron. Both squadrons flew at a similar intensity as far as monthly hours were concerned, about 30 hours per established aircraft regardless of the number of SAR scrambles. This left about 15 hours per pilot for SAR training, instrument and night flying and engine-off landing practice.

There was no promised night flying rescue task because the Whirlwind lacked appropriate equipment such as auto-stabilisation, target illumination, radar etc for the role in complete darkness. The policy was therefore to maintain a 15-minute readiness throughout the hours of daylight and a one-hour readiness at night. In practice most of the night operations requested were in fact carried out.

The Whirlwind was, by modern standards, an unsophisticated single-engined aircraft. It was relatively under-powered and in its early days was not particularly reliable; several ac ditched or crashed; on 30 Aug 1955 XJ 436 flown by OC 22 Squadron, Squadron Leader Powry, ditched during a National Press demonstration with a Marine Craft Launch. One month later XJ 434 flown by Flying Officer Cox ditched during wet winching training. A further seven Whirlwinds of 22 Squadron alone crashed before all Whirlwinds were grounded temporarily in December 1967 following the fatal crash of a Queen's Flight Whirlwind. However this was not to be the end of Whirlwind accidents, although the rate of accidents was greatly reduced as it matured in to Service. Nevertheless, as with all RAF helicopter crews, the aircraft was operated to an exceptional standard. The limitations of its range, power and lift capability as well the shortness of its winch cable were overcome by the hard work and dedication of its crews in their sound training, development of SAR techniques and equipment, and often by sheer personal courage.

A large number of gallantry and professional awards were made to the RAF SAR Helicopter crews. These including six George Medals (GM), fifty one Air Force Crosses (AFC) and Medals (AFM) and ninety two Queen's Commendations for Valuable Service in the Air (QCVSA) and Queen's Commendation for Bravery in the Air (QCBA) and 86 AOC-in-C's and AOC's Commendations (these were awarded to the groundcrew as well as aircrew). Many Civil and foreign awards were also made. In general Pilots (Aircraft Captains) were recognised for their outstanding perseverance a and aircraft handling skills in atrocious flying conditions. Winchmen were awarded medals for their courage and fortitude, often at great risk to their own personal safety. Navigators were recognised for their role in making the rescue possible by their calm professionalism and ingenuity, without which the SAR helicopter team could not operate. It is believed that the highest number of awards for a single RAF SAR helicopter operation was for the rescue of sixteen seamen from the deck of the sinking Motor Vessel Amberley on 2 April 1973.

Three Whirlwinds, one from Leconfield and two from Coltishall, flew through heavy snowstorms and seventy-knot winds to complete the rescue; the rescue was immortalised by a painting by the aviation artist Rex Flood.

The pilot from Leconfield (Flight Lieutenant Bernard Braithwaite ) was awarded the AFC, all three Winchmen (Master Air Electronics Operator Dinty More, Master Signaller Ken Meagher and Flight Sergeant Dick Amor) were awarded the AFC/AFM and the three Winch Operators (Master Navigator Ron Dedmen, Flight Lieutenant Tony Cass and Flight Lieutenant Don Arnold) were awarded Queen's Commendations for Valuable Service in the Air; however, no awards were made to the two pilots from Coltishall (Flight Lieutenant Jim Ross and Flight Lieutenant Ian Christie-Miller).

In general this apparent inequality in the issue of awards has generally been accepted. However, in some cases the disparities have caused some consternation and disquiet amongst the crews; generally those receiving higher awards supporting the call for higher recognition of those crewmembers receiving lower awards or no award at all.

It is true to say that the winchman placed his personal safety and often his life at risk every time he went over the side of the aircraft on the end of the winch cable. Training m methods were developed to minimise these risks.

Where possible, the aircraft was hovered at a low height over a flat surface before the winchman was winched out. The aircraft was then climbed to its operating height as the cable was winched out to maintain the winchman at a safe height above the ground. The pilot manoeuvred the aircraft to a point overhead the incident under the directions of the Winch Operator who also operated the winch to maintain the Winchman at a low height over the ground as he was carried to the survivor. Recovery of the winchman and survivor was effected by the reverse of this method with the aircraft being lowered as the winchman and survivor were winched in. This safe method of operating prevented some serious accidents; even in training it was not unknown for the winchman to fall off the cable through failure of equipment or procedures. Serious consideration was also given to the ever-present possibility of engine failure or the inability to hold a hover in turbulent wind conditions. With the winchman at a safe height above the surface the Winch Operator could cut the cable, severing the Winchman from the stricken helicopter, reducing the risk of serious injury, leaving the pilot to crash land or ditch the aircraft as best he could. This safe practice of winching was religiously adhered to, where possible, throughout the Whirlwind and Wessex eras.

Indeed some of the notable rescues carried out successfully that merited the award of an AFC/AFM to Winchmen were in instances where this procedure was not possible. For example; on 19 May 1974 Flight Sergeant John Donnelly won the first of his two AFMs for being carried on a 200ft-rope extension attached to the winch cable eight hundred feet above the cliff floor at Clogwyn on Snowdon. He was then swung as a pendulum to gain access to an injured survivor below an over-hang. His second AFM was awarded for a night rescue from a yacht in heavy seas during which he used a rope to assist with the deployment of the survivors to enable the whirlwind to winch safely away from the yacht's mast. This was an impromptu invention of the hi-line, which was l later to become standard equipment with the Sea King to assist with rescues from ships and dinghies. Unfortunately it is not possible to re-tell every notable rescue. Indeed many momentous rescues were completed successfully without any publicity and the consequent public recognition of the crews' deeds. Those receiving Service and Public acclaim were often awarded medals or commendations. In the last forty eight years of RAF SAR helicopter operations only six George Medals have been awarded, the highest Level of award yet given to RAF SAR helicopter crews, for the most exceptional feats of bravery and fortitude (the George Medal is a "Level Two" award whereas the Air Force Cross is a "Level Three" award).

Image courtesy of the RAF Club

The Wessex HC2 was introduced into squadron service with No 18 Squadron and No 72 Squadron at Odiham in 1964. The Wessex was employed in the Support Helicopter role but it was used to hold SAR cover during the grounding of the Whirlwinds in December 1967.

In 1974 two Wessex HC2s of No 72 squadron were modified to the SAR role at Fleetlands. The crew sent to collect the first aircraft (XT602) had difficulty in finding it as it had been painted in the usual 72 Squadron, camouflage paint scheme rather than the SAR bright yellow; however this was soon rectified. D Flight 72 Squadron was to replace the Bristow Helicopters Ltd Whirlwind Series 3 aircraft contracted to the Coastguard at Manston. The local population was again concerned at the change from Bristow Helicopters Ltd to the RAF but was assured by the Ministry of Defence that the SAR Flight at Manston was to be a permanent detachment. The Flight actually remained at Manston for a further twenty years before being moved to Wattisham, along with the closure of Coltishall. The crews trained at the Search and Rescue Training Squadron RAF Valley before taking over the SAR standby in October 1974. The Wessex had many advantages over its predecessor. In many ways it was a like a large Whirlwind in that it had a large main cabin suitable for casualty handling with a cockpit separated from and above it. However, it was a much more robust aircraft with a heavy-duty, tail wheel, tricycle undercarriage. It had two powerful Gnome engines with a very good single engine capability. It was significantly faster, it had a much greater lift capacity and an enhanced radius of action. Its only perceived disadvantage was that being heavier it needed to be hovered higher over the sea and was not quite as manoeuvrable as the Whirlwind. Conversely it had a good Auto-Stabilisation Equipment system which made it a stable winching platform and improved its ability for transit in cloud. Its ability to operate in poor visibility and at night was improved by fitting a radar altimeter; however, without a full Auto Pilot system, it was still not designed to be operated over the sea at night.

Nearly two years were to pass before more Wessex helicopters were introduced into SAR duties. In 1976 No 22 squadron was partly re-equipped with Wessex HC2s in the SAR role. C Flight 202 Squadron at Leuchars became B Flight 22 Squadron in April 1976. D Flight 72 Squadron at Manston became E Flight 22 Squadron in June 1976 and C Flight 22 Squadron's Whirlwind 10s were replaced by Wessex HC2s at Valley in June 1976. A and D Flights 22 Squadron remained at Chivenor and Brawdy with their Whirlwind 10s.

202 Squadron maintained an all-Whirlwind 10 fleet at A Flight Boulmer, B Flight Leconfield, C Flight Coltishall and D Flight Lossiemouth. In most respects the Wessex was operated i in a similar manner to the Standard Operating Procedures of the Whirlwind, their crews exploited the Wessex's advantages to the full. The Wessex became a very capable and versatile search and rescue helicopter, although limited because it was still not normal to operate the aircraft over the sea at night. Initially the winch fitted to the Wessex had 100ft of cable. Instead of a rope extension to the winch cable, previously used by the Whirlwind, a formal 120ft tape (attributed to Flt Lt Mike Ramshaw) was introduced to extend the effective length of the cable. The tape was used on both the Wessex and the Whirlwind. However, in 1977 a 300ft cable was fitted to the Wessex negating the necessity for the tape. The Wessex remained in SAR service until its final replacement by the Sea King Mk 3 at Valley in June 1997 and by the introduction of the Griffin, with the transfer of the Search and Rescue Training Unit at Valley from 18 Group to the Defence Helicopter Flying School, on 1 April 1997.

From the outset in 1953 it was envisaged that the two separate SAR Helicopter Squadrons would act independently. 275 Squadron was established in 13 Group Fighter Command and 22 Squadron in 19 Group Coastal Command. Each had its own training and engineering organisations. The Sycamore was operated with a crew of two while the Whirlwind had a crew of three. The two squadrons started to be drawn together in May 1958 when 275 Squadron was transferred to 18 Group Coastal Command. However, it was not until the introduction of the Whirlwind Mk 2 to both Squadrons that the training for both squadrons was brought together; the Training Flight of 22 Squadron at St Mawgan having achieved Operational Training Unit status in July 1959. In 1962 the Central Flying School (Helicopters) (CFS(H)) took over the SAR training at its detachment at Valley. The Operational Training Unit was closed and the QHIs from St Mawgan then formed the helicopter element of the Coastal Command Categorisation Board. On 27 November 1969 Coastal Command was disbanded at a Stand-Down ceremony at St Mawgan and on the following day 19 Group was re-titled Southern Maritime Air Region (SOUMAR). From then on both SAR Squadrons came under 18 Group of Strike Command.

From October 1957 the Squadron Headquarters for 275, 228 and 202 Squadrons had been at Leconfield. From June 1956 until April 1974, 22 Squadron's Headquarters had been at St Mawgan and then at Thorney Island. However, in January 1976 both Squadrons were brought together under the Search and Rescue Wing at Finningley. The 18 Group Standardisation Unit (Helicopters) (18 GSU(H)) also moved from Northwood. The Headquarters of the Search And Rescue Wing was in the "Green Shed", an apt description for a series of pre-fabricated offices and corridors, housing the Officer Commanding, the Wing Adjutant and secretarial staff, the Officers Commanding 202 and 22 Squadrons with their Training Officers (Pilot, Navigator and Winchman) and the 18 GSU(H). The Second Line servicing for all the RAF SAR helicopters was carried out at the SAR Engineering Wing Headquarters across the road from the "Green Shed". The whole of the organisation of the front-line RAF SAR Force had the advantage of being contained under one roof. The Squadron Training Officers and the 18 GSU(H) worked closely together to improve flying and operational standards, Standard Operating Procedures and equipment. The SAR Wing saw the introduction of the Wessex into SAR service in 1976 and the Sea King in 1978/9.

In December 1992 the SAR Wing was disbanded with the closure of Finningley. The Headquarters element of the Wing moved to St Mawgan under the Command of the Station Commander RAF St Mawgan as the SAR Force Commander. The Headquarters of 22 Squadron returned to St Mawgan and the 202 Squadron Headquarters moved to Boulmer. The 18 GSU(H) moved back to Northwood until February 1997 when it also moved to the SAR Force Headquarters St Mawgan. The Training Officers of the Squadrons, although posted to their respective Squadron Headquarters, tended to operate and travel from their chosen dispersed Flight locations in an attempt to reduce the inevitable disruptions to their family life that the nomadic existence of the training officer entailed. In September 1997 Headquarters 22 Squadron moved to Chivenor. The SAR Helicopter Force was again dispersed although it retained the ethos of a coherent Search And Rescue Force.

Image courtesy of the RAF Club

By the mid-1970s it was apparent that a new helicopter was needed if the RAF's Search and Rescue Wing was to proceed with confidence towards the end of the century. There was a requirement for an all-weather long-range helicopter; "one designed to take the medals out of Search and Rescue". Sixteen Sea King HAR 3 helicopters were ordered from Westland Helicopters Ltd. The first came into service in 1978. 202 squadron was re-equipped with Sea Kings while 22 Squadron maintained its mixed fleet of Wessex and Whirlwind. The first Sea King Flight was formed at D Flight Lossiemouth in August 1978; this was followed by A Flight at Boulmer, C Flight at Coltishall and B Flight at Brawdy. Each new Flight's crews were trained as a unit at the RAF Sea King Training Unit at RNAS Culdrose.

The Sea King introduced a major enhancement in search and rescue capability. It was a large helicopter with a significant fuel load, sufficient to maintain the aircraft operational for about six hours. Its maximum speed varied, with all up mass, up to 125 knots. The most significant operating improvement of the Sea King was in its all-weather and night operability over the sea. For this the co-pilot had a Decca-Doppler Tactical Air Navigation System (TANS) computer as well as a full range of radio navigation aids. The radar operator had a light weight helicopter search radar used for safe obstacle clearance during transit over the sea and, with its radar plot driven by a Radar/TANS interface giving the radar operator a moving radar map for close tactical navigation. Where a known feature could verify the radar position it was used for the control of search patterns. The aircraft was fitted with an autostabiliser and a simplex autopilot, comprising a height hold and automatic transition system, capable of automatically flying the aircraft to and from the hover over the sea. An Auxiliary Hover Trim system, operated by the Winch/Radar Operator, was used for final detailed manoeuvring within the hover. It had a limited icing clearance, sufficient for icing to be encountered and then avoided. It had a large passenger carrying capacity with sufficient area in the cabin for the carriage and use of modern first aid and life support systems. It even had a small galley with a water heater and space for holding snack meals and drinks.

Operation of the Sea King was significantly different from that of the Whirlwind and Wessex. Primarily instead of crew of three it had a crew of four; pilot, co-pilot, radar/winch operator and winchman. Traditionally the captain occupied the right hand seat as first pilot responsible for flying the aircraft. The co-pilot was responsible for normal navigation and aircraft systems management; he was also responsible for operating the radios and for general operations co-ordination during rescues. However, the aircraft captain had the opportunity to choose from which seat he was to operate and there were many occasions when the Operational Captain was in the left hand seat during an airborne diversion to an SAR operation.

Questions were asked within the first year of the Sea King's operation whether a single pilot and a navigator, as co-pilot, could operate the aircraft. This idea was quashed following the Squadron Commander's invitation to the Air Officer Commanding 18 Group (a Navigator) to handle the flying controls following an autostabiliser equipment failure. The autostabiliser equipment system had been trimmed away from the central position causing a large attitude change in pitch and roll as the autostabiliser was disengaged making the aircraft difficult for a non-pilot trained operator to handle. A Senior Non-Commissioned Officer Air Electronics Operator Radar/Winch Operator replaced the Navigator/Winch Operator. His duties were to guide the aircraft safely during transit over the sea and to place the aircraft in a position from where a transition down to the target could be made. At the rescue scene he left the radar-shack to become the winch operator. Additionally, with the Auxiliary Hover Trim joystick, he could position the aircraft finely should the pilot have insufficient references to maintain an accurate hover over a target in the sea. The Winchman's duties remained largely the same except that with a larger cabin a greater range of first aid and life support equipment could be carried and over the years the Winchman's expertise in first aid has increased to "Para-Medic" standard. Previously when dealing with an injured survivor the winchman did his best to stabilise the casualty sufficiently to be winched and carried a short distance to hospital. Now, with the possibility of being well over two hours from medical assistance, the winchman will spend more time with the casualty before winching him into the aircraft and tend to his medical needs during longer transits. Additionally, with the Sea King's easy access between the cabin and cockpit the winchman is available to assist the pilots with detailed navigation and radio management (and making good use of the galley).

The Sea King was capable of carrying out the whole of the range of SAR operations of the Whirlwind and Wessex. However, its size, with increased down wash, made it necessary for it to be hovered over the sea at about twice the normal operating height of a Wessex and three times the operating height of the Whirlwind. This made precise hovering more difficult; nevertheless, its mass and inertia made for a stable winching platform, provided that the autostabiliser equipment authorities were trimmed to the central position and the pilot made small control inputs. Outside these parameters the aircraft was more difficult to control smoothly. In the first year of operation different operating heights were tried. Experience quickly showed that when hovering at the normal 40ft above the sea on a calm day the down wash was sufficient to blow a single-seat dinghy upside-down with it's occupant still inside. Conversely the Sea King still had to be flown at Whirlwind heights when operating with the small RNLI Life Boats.

Eventually a normal operating height of 50ft over the sea evolved; this also has the major benefit of keeping the aircraft clear of most of the sea spray raised by the down wash. Salt ingestion into the engines can reduce their performance leading to engine failure. For mountain operations it quickly became the practice to fuel the aircraft to relatively low fuel states to ensure an adequate thrust margin; preferring to refuel the aircraft if necessary for longer range operations. Moreover, despite claims by Wessex crews to the contrary, the Sea King was just as effective in the mountains as the Wessex. Indeed when operated at similar fuel weights, to give it an equivalent patrol time as the Wessex, the Sea King had a greater power margin available than the Wessex.

One additional problem that was encountered with the start of Sea King operations was a significantly large increase in the level of static electricity generated by the aircraft. From the outset, static electricity discharges from the Whirlwind were encountered, indeed Flight Sergeant Eric Smith GM, had to suffer the effects of static electricity discharges to gain a handhold on the "Jeanne Gougy". Nevertheless on an average day the effects of static electricity discharges through the winchman were generally considered to be a normal operating hazard. The level of static electricity generated by the Wessex was greater than that of the Whirlwind, yet generally it remained within tolerable limits. Static electricity in helicopters builds up as a result of the movement of the rotor blades through the air and friction in other moving components such as engines and gearboxes. The voltage generated in a helicopter is largely a factor of the aircraft's height above the surface. The amount of static charge held by the helicopter, and its rate of generation depends on the environment the aircraft is operating in. On a dry day the level and rate of static charge generated is relatively small and generally holds no major problems. However when operating underneath cumulonimbus clouds the electrical charge generated and the rate of re-generation of the charge is very high and can be lethal; cases of serious injury caused by electrical burns to the winchman have been recorded by the Royal Navy and other Foreign Services operating the Sea King. At first the RAF Sea King Winchmen attempted to manage the problem. However after several cases of serious electrical shocks, not only to the winchman but also to lifeboat crews who latterly refused to go anywhere near the winchman until he had released himself from the winch cable, the problem was investigated by scientists who visited Coltishall to make a practical assessment of the problem. The Winchmen were invited to wear various items of equipment including Faraday Cages and immersion suits, boots and gloves with copper wire attached to conduct the charge away from the winchman and discharge it on contact with the surface. None of these proved to be practical. The fitting of static wick dischargers to the aircraft was suggested by the aircrew as a means of reducing the overall charge; however, this was initially discounted by the scientists because it would reduce the time from static discharges before the voltage re-built to previous levels. Eventually a trial fit of static wick dischargers, fitted to the main rotor blades and horizontal stabiliser, was authorised and proved to be effective in reducing the overall problem and remains part of the aircraft fit. At the same time the "zapper snapper" static discharge lead was invented and tried at Coltishall. Despite proving to be very effective in reducing electrical shocks to the Winchmen, its use was initially prohibited, because it had not been cleared by the engineering authority. This was soon rectified and the "zapper snapper" remains standard winchman equipment. The Sea King's static electricity problem is now manageable; however, crews still avoid winching under cumulonimbus clouds or in other areas of probable atmospheric electrical activity.

The Sea King had not been in service for long before three major incidents occurred. The first was on the night of 1 October 1980, after the first standby aircraft from Lossiemouth and a Coastguard S61 helicopter were unable to affect a rescue from the stricken Motor Vessel "Finneagle". A scratch second standby crew, Flight Lieutenant Mike Lakey, Flight Lieutenant Dave Simpson, Flight Lieutenant Bill Campbell, Sergeant Rick Bragg and Doctor, Squadron Leader Hamish Grant, scrambled to assist the crew of the vessel. Mike Lakey and his crew rescued twenty-two persons from the burning and exploding ship. For this act of gallantry Mike Lakey was awarded the George Medal; Dave Simpson was awarded the Queens Commendation For Valuable Service In The Air, Bill Campbell was awarded the Air Force Cross, Rick Bragg was awarded the Air Force Medal and Hamish Grant was awarded the Queen's Commendation for Brave Conduct. The Sea King had been used for a rescue that no other single helicopter in service could have achieved.

Six weeks later, on 18 November 1980, two American A10 aircraft collided in mid air eight miles North West of Coltishall. One pilot had ejected immediately and was later picked up by the second standby aircraft and taken to Norwich. The other aircraft remained airborne for a short time before ejecting and parachuting into the sea off the North Norfolk coast. The first standby aircraft diverted to this accident. On arrival at the scene it was found that the pilot had failed to separate himself from his parachute and was being dragged through the sea in the forty-five knot winds. Without consideration for his own personal safety Master Air Loadmaster Dave Bullock attempted to rescue the pilot. During the rescue attempt the parachute inflated, lifting the pilot and Dave Bullock from the water. Tragically, the winch cable snapped. Instead of saving himself from an impossible rescue Dave Bullock continued to support the pilot until his own strength was lost. Dave Bullock died alongside the pilot. For his supreme sacrifice in this tragic rescue Dave Bullock was posthumously awarded the George Medal.

The last of the three incidents has consequences to the present day. In May 1982 one Sea King was shipped to Ascension Island to assist with moving passengers and stores between Ascension Island and the ships travelling to and from the Falkland Islands, under the Officer Commanding Naval Party 1222, as part of Operation Corporate. The detachment lasted until September 1982. However, in August 1982 C Flt 202 Squadron, as a whole, was detached from Coltishall to the South Atlantic. On 4 August 1982 three grey painted Sea Kings were placed in a hangar, built from containers, on board a ship at Marchwood and sailed, along with the ground crew, to Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands, arriving on 27 August. The aircrew flew by VC10 to Ascension Island and then boarded the "Norland", arriving in the Falkland Islands on 24 August. The permanent detachment of Sea King aircraft and crews for search and rescue and logistics duties in the Falkland Islands had begun. The detachment posed a strain on SAR resources. The Flight at Coltishall was taken over by 22 Squadron flying the Wessex, where for the first year crews were taken on detachment from Leconfield and Manston. However in August 1983 F Flight 22 Squadron was formed at Coltishall and remained there until C Flt 202 Squadron returned with Sea Kings in September 1985, the Falkland Island Flight having been renumbered as 1564 Flight. In mid June 1985 the first of three new Sea King Mk 3s arrived to augment the Sea King fleet, returning it to its previous UK strength. Additional crews were posted to 202 Squadron to ease the burden of the Falkland Island detachment. However, a general shortage of aircrew in the RAF as a whole and the helicopter force i in particular caused manning shortfalls reducing the effectiveness of the additional establishment of Sea King crews.

Further redistributions of the RAF's Search And Rescue Helicopter assets continued to meet station closures and SAR cover requirements. Over 31 August / 1 September 1988 E Flt 22 Sqn (Wessex) moved from Manston to Coltishall and was replaced by C Flt 202 Sqn's (Sea King) move from Coltishall to Manston. In April 1993 B Flt 22 Sqn Leuchars (Wessex) was disbanded despite significant opposition from the local community. In July 1994 B Flt 202 Sqn Brawdy (Sea King) disbanded and B Flt 22 Sqn was reformed at Wattisham with Sea Kings. At the same time E Flt 22 Sqn Coltishall and C Flt 202 Sqn Manston were also disbanded. This time C Flt 202 Sqn's departure from Manston was celebrated with a congratulatory demonstration of support and thanks from the local population.

The last major enhancement to the RAF's SAR Helicopter force was in the purchase of six Sea King HAR 3As. In May 1996 the first Sea King Mk 3A course was started at the Sea King OCU at St Mawgan. However it was abandoned after three weeks because of problems with the height programmes of the flight path control computer. Further development of the systems was completed and in May 1997 the first Sea King Mk 3A course was completed. The crews from that course took the aircraft to Chivenor to commence SAR standby. The Sea King 3As was also deployed to Wattisham in July 1997. The Sea King Mk 3s from Wattisham replaced the last Wessex from Valley to complete a Sea King only SAR helicopter Force comprising 22 Squadron with Mk 3As at Chivenor and Wattisham and Mk 3s at Valley and 202 Squadron with Mk 3s at Boulmer, Lossiemouth and Leconfield.

The Mk3A was designed to be a quantum leap in autopilot controlled procedures for the SAR force. To do this it was fitted with a duplicated stabilisation and auto pilot system, in creasing the range of options available to the flying pilot whilst airborne. In the Mk3, the pilot needed to fly the ac manually to a suitable point to let down to a target. He could be assisted by a rudimentary height hold down to 200ft and from there, once in to wind, an autopilot programme could be engaged to fly the ac down to a height band of 30 to 60ft. Once in the hover, the pilot would manually close with the target before re-engaging the auto hover mode. In the Mk3A the designer decided that this could be improved on. Firstly, the stabilisation system was changed to improve its characteristics. Secondly, a flight path computer, autopilot, was added that could carry out whole range of functions; not just an auto hover mode. Thirdly, to improve the system still further, a sophisticated navigation suite was added which could be tied into the flight path computer. Redundancy was also built into the navigation suite by having four independent navigation methods comparing their derived positions. The co-pilot, as operator, could decide which had the best information and therefore could influence the accuracy of navigation.

With all systems on line and the aircraft airborne the flying pilot could engage the Flight Path computer. The system then flew the aircraft's speed height and heading. This could be in a simple manner, just maintaining the speed, height and heading, or the heading could be tied into the navigation suite. A flight plan of different landmarks could be programmed from an extensive 3500 entry database. The aircraft would then follow the prescribed route without the pilot having to touch the controls. Once at the final destination the pilot still had to land the ac; however, on long over-water rescues, this is a major enhancement in reducing crew fatigue.

Over the water the aircraft's automatic modes, for poor weather or night operations, were also enhanced. Below 1000ft, the aircraft now had a Radar Altimeter hold which could be operated very easily. Once at or below 750ft, if a target was over-flown, the aircraft could be letdown automatically to the 50ft hover by pressing a single button. Once the button was pressed the aircraft took control and worked out a pattern to fly to letdown to the hover next to the target.

Further improvements were made to the "normal" methods of getting to the 50ft hover. The aircraft could be let down from any height below 750ft, thus increasing the flexibility of the modes of operation. This auto letdown capability was a 'hands-off' automatic flight from any air speed down to zero ground speed at 50 ft. In the Mk 3 this needed to be a straight-line approach into wind for the ac to be able to fly it. In the Mk 3A, not only could the system accept the aircraft's being out of wind slightly but also the aircraft can be forced to move left or right at the same time during its letdown. This permitted the aircraft to be flown closer to the target on letdowns. Furthermore, should a straight approach not be practical, both aircraft were a able to fly a curving letdown. In the Mk3 the pilot had to control the direction and speed of the aircraft until the timed height programme had finished. In the Mk3A the pilot still controlled the speed and direction but once he had finished manoeuvring he was able return control to the flight path computer to complete the letdown.

Unfortunately there was a price to pay for these improvements. The Mk 3 was a joy to hover in any situation. The controls were light and sensitive allowing precision placement of the ac. The Mk 3a was not so easy to fly. To allow all the 'Gucci' equipment to work small "gaps" had been placed in the control runs so that computer inputs could be differentiated from pilot inputs. This equated to a dead-band when trying to hover the ac. As a result the controls became less sensitive and the ac tended to wander around in the hover. This could be overcome with pilot practice. Unfortunately, it took more practice to hover a Mk3A competently than it did to hover a Mk3. For this reason alone the aircraft gained a poor reputation in its early years. It was only later, as the early "pioneers" of the Mk3A return to fly the MK3, that they realised it was a small price to pay for what was a quantum leap forward in SAR safety and reliability.

Initially SAR training was conducted on an ad-hoc basis on the squadrons. Pilots were trained in aircraft handling skills but winch operators and Winchmen were left largely to their own devices to develop their own procedures and skills. In November 1958, with the departure of A Flt 22 Squadron to Chivenor, a Training Flight was formed as part of the HQ Flight at St Mawgan. In July 1959 the Training Flight became an Operational Training Unit and provided training and standardisation for both 228 and 22 Squadrons.

In 1962 CFS(H) 3 Squadron, was established at RAF Valley, as a permanent detachment from Ternhill, for SAR training for all helicopter students in general as well as SAR crews in particular on the Whirlwind Mk 10.

The unit also trained its own Qualified Crewman Instructors (QCI). With the move of CFS(H) from Ternhill to Shawbury in September 1977 and with the formation of 2 Flying Training S school (2 FTS) for the training of Basic helicopter students, 3 Squadron CFS(H) was renamed the Search and Rescue Training Squadron (SARTS) of 2 FTS. In December 1979 the responsibility for SAR training at Valley was transferred to 18 Group and SARTS was renamed the Search and Rescue Training Unit (SARTU). In February 1981 the Whirlwind Mk 10s were replaced by Wessex Mk 2s and SARTU remained the central unit for training for all basic helicopter students, SAR QCIs and operational SAR crews.

2 Flying Training School at Shawbury was disbanded on 1 April 1997 and the Defence Helicopter Flying School (DHFS) was formed to train helicopter pilots for all three Services. SARTU was transferred to the DHFS and equipped with the Griffin as the RAF's advanced rotary wing training aircraft. SARTU's role remained largely the same, notwithstanding that all Qualified Helicopter Crewman Instructor (QHCI) training had been transferred to CFS(H) in 1994, from there Crewmen Graduated from CFS(H) as B2 QHCIs. Until the introduction of the Sea King in 1978, all new SAR crews were posted directly from Valley to their operational Flights. From then crews going on to Sea King Flights continued to received their full SAR training at Valley before being sent to the RAF Sea King Training Unit/Operational Conversion Unit (OCU) for conversion to the Sea King.

The RAF Sea King Training Unit (RAF SKTU) was established at RNAS Culdrose in February 1978. Initially it formed as a Royal Navy Squadron under the command of a Royal Navy Commander staffed by a mixture of RN and RAF instructors. Its first course commenced in February 1978 to train its QHIs and QCIs on Sea King operations. Its primary task was then to train the operational crews to fill the four Sea King SAR flights at Lossiemouth, Boulmer, Coltishall and Brawdy. The comprehensive course lasted for approximately four months and for the first time, for RAF helicopter crews, flight simulators formed an important element of their training. By October 1979 all four Sea King flights were operational and the size of the courses fell from four full crews to a couple of pilots and rear crew only. The RAF SKTU became the RAF Sea King Training Flight of 706 Naval Air Squadron (NAS) and in January 1982 the RAF SKTU separated from 706 NAS to become a small but independent lodger unit at RNAS Culdrose until it moved to St Mawgan in April 1993. On 1 April 1996, along with the policy of giving Operational Conversion Units and Training Squadrons Reserve Squadron status, the RAF SKTU became 203 (R) Squadron. In December the Sea King Simulator was opened at St Mawgan to enhance the training of both 203 (R) students and operational squadron aircrew.

Routine training on the SAR Helicopter Flights was the responsibility of the Squadron Training Officers. They were required to raise individual aircrew's abilities to an acceptable operational standard and then to improve those skills to the highest level possible. For many years an individual was awarded a category which reflected his flying and operational ability. The categories ranged from a "D Category", (a probationary category) that had to be upgraded to a "C Category" (average) within a short period of time (six to nine months). After a longer period of time above average crews were encouraged to upgrade to a "B Category". Those very few individuals who displayed the highest, exceptional ability were awarded an "A Category" for which they were entitled to wear a "Command Crew" and later an "A Category" badge on their flying suits. The hierarchical categorisation system had the positive benefit of encouraging individuals to work to achieve higher standards. Moreover, during a period in the mid 1980s when the categorisation system was abolished and replaced by an Operational/Non-operational rating it was noticed that the general standard of training and operational ability fell and for some individuals it fell to just the minimum required to maintain their operational status. Fortunately the categorisation system was restored and with it the overall standard of training and operational effectiveness. In 1996, to bring the SAR Helicopter Force in line with the Nimrod Force, the more direct "D to A", flying and operational ability, labelling of categories was replaced by one related to an individual's operational status and ability; ie Limited Combat Ready, Combat Ready, Combat Ready (Advanced) and Combat Ready (Select). In many respects both systems reflect similar abilities; however, in some manner it was felt that the new system names failed to reflect the actual tasks required of the crews. In particular the term Limited Combat Ready had no effective meaning in that Limited Combat Ready crew members were placed on operational SAR standby in exactly the same manner as Combat Ready crew members. The new system also lost some of the element of encouragement for crews to achieve higher standards. Fortunately the calibre of SAR crews has overcome this anomaly and generally there is a healthy ethos of achievement in the SAR Helicopter Force.

Most directly the flying and operating skills of the aircrew are as a result of the success of the training and standardisation organisations of the SAR Helicopter Force. The central training organisation for SAR helicopter crews was formed with the establishment of the Operational Training Unit at St Mawgan in July 1959 and with the introduction of the Whirlwind Mk2 to both SAR helicopter squadrons. In 1962 the SAR training task was transferred to the CFS(H) Squadron detachment at Valley. At the same time the helicopter element of the Coastal Command Categorisation Board was formed. This small unit was transferred to 18 Group in November 1969 with the disbandment of Coastal Command and became the 18 Group Standardisation Unit (Helicopters). In 1995 elements of 11 Group and 18 Group combined at Northwood to form 11/18 Group and the 18 GSU(H) became part of the 11/18 Group Helicopter Standardisation Unit (11/18 HSU). For a six month period over 1996/1997, after the failure of the Sea King Mk 3A's initial introduction into service, the Sea King element of the 11/18 HSU stood down to assist with the formation of the Mk 3A Operational Evaluation Unit at St Mawgan. A further major reorganisation of Strike Command on 1 Apr 1999 saw the disbandment of 11/18 Group and the formation of 3 Group. The RAF SAR Helicopter Force was transferred to 3 Group and the Sea King element of the 11/18 HSU was renamed the 3 Group Helicopter Standardisation Unit (3 Group HSU). The standardisation units were responsible for the formulation and writing of Standard Operating Procedures and the standardisation and categorisation of the SAR helicopter crews, not only in the UK but also, by request, to overseas RAF and Foreign and Commonwealth SAR Helicopter Units.

There have been three major detachments of UK based SAR Helicopters to overseas theatres of operation, (22 Squadron from St Mawgan to Christmas Island, January 1957 to January 1958: 22 Squadron from Manston to El Adem to reform 1564 Flight from March 1969 to October 1969: and 202 Squadron from Coltishall to the Falkland Islands from August 1982 to the present); as opposed to squadrons and flights overseas, established for SAR duties to cover fixed wing operations.

It is not within the scope of this short account of UK Search SAR helicopters to detail the history of these units. Short accounts of the Christmas Island and the El Adem detachments and of the established overseas SAR Squadrons and Flights are available in Wing Commander J R Dowling's two-volume account of "RAF Helicopters the First Twenty Years", Air Historical Branch 1987.

After the Falkland Islands war it was decided that the UK would hold a deterrent force in the South Atlantic. In addition to ground troops defending the Falkland Islands, the RAF detached personnel to maintain a forward operating base at Port Stanley to enable the transport air-bridge to be maintained and defended by fighter aircraft. Chinook helicopters from 18 Squadron were deployed to assist with troop and load carrying, particularly for the building of radar stations. Bristow Helicopters Ltd was contracted to provide S61 aircraft for passenger and internal load carrying tasks. C Flight 202 Squadron from Coltishall was deployed to provide SAR cover for the Islands as a primary role and to assist with the support tasks of the Chinooks and the S61s as a secondary task.

Three Sea King Mk 3 aircraft were painted grey (nicknamed "Grey Whales") and fitted with various modifications including Radar Warning Receivers, Omega Navigation systems, cockpit night vision goggle compatibility and an eight thousand-pound under-slung load beam. In August 1982 the aircraft were loaded on the Container Vessel "Beizant" and shipped, along with the ground crew, to Port Stanley. The aircrew flew by VC10 to Ascension Island and then boarded the "Norland" to sail to the Falkland Islands, arriving a few days before their aircraft. Initially the SAR Flight was set up at Port Stanley airfield but in March 1983 the Flight moved to Navy Point, across the harbour from the town of Port Stanley. The Flight was accommodated in portacabins with the aircraft housed in tented hangars; the aircraft dispersals were made of pierced steel planking. The domestic accommodation was also in portacabins some few hundred yards away from the Flight accommodation. Access between the two was via a peat bog; however, quickly a large number of wooden pallets were acquired and laid end to end to form the "pallet path" linking the two.

As near as possible the Flight continued to operate as it had done in the UK. However, although many notable rescues were completed successfully, the Flight's secondary role of troop and load carrying occupied nearly all of the Flight's resources. Soon the Flight's efforts were limited by aircraft availability. This was mainly due to the high rate of task flying and the completion of routine servicing schedules. The Aircraft Servicing Flight at Port Stanley Airfield carried out the second line servicing task for the Sea Kings up to and including Minor Servicing. Also the Falkland Island aircraft were the first RAF Sea Kings to suffer cracks in the "290 frame" (a standard fatigue cracking of one of the main structural frames of the Sea King, holding part of the main gearbox supports). Additionally in August 1983, one aircraft had to be repaired following a heavy arrival at the refuelling site at Port Stanley airfield. The helicopter had landed tail rotor first, followed by a heavy landing on the main wheels, which broke off one of the sponsons. The helicopter was recovered to the hover, despite a seriously damaged tail rotor. The pilot selected the wheels up and landed the aircraft safely on the eight thousand-pound load beam without further damage.

The rate of secondary tasking continued to the extent that the secondary, support task was given a higher priority over the Flight's primary role other than for actual SAR

missions which required a dedicated SAR helicopter. Essential medical evacuation tasks were passed on to the Army Air Corps helicopters. Servicing schedules had to be extended to maintain the

aircraft flying on support tasks. At one stage the Flight had the one remaining aircraft serviceable with only ten flying hours remaining to the end of an extension to a Command extension to a

scheduled servicing. This had to last for up to four days until another aircraft was returned from servicing at Port Stanley; moreover, six hours was needed to be reserved for SAR operations

only to allow for the possibility of a SAR task at the edge of the Falkland Island Protection Zone. However, one bright Sunday morning on 27 November 1983 all three Sea Kings were serviceable

at the same time, for one short positioning sortie only, and the opportunity was taken to escorted one aircraft to Port Stanley for its scheduled servicing by the other two.

Tasking continued unabated and the Flight remained short of hours and with generally only one aircraft serviceable at any one time until March 1984.

During this time the Royal Navy was unable to accept the additional task of helicopter Maritime Radar Reconnaissance (MRR) of the Falkland Island Protection Zone because of a shortage of Sea King engines. Consequently, the Flight was tasked to carry out the daily MRR task. This additional task took priority over the Flight's Search and Rescue Role. The MRR task involved a lengthy sweep search over the sea using the aircraft's radar. While the Flight's Sea King was airborne the Royal Navy was tasked to hold Search and Rescue standby with their ship-borne Sea Kings. Unfortunately, this arrangement was not always as successful as had been intended. On two occasions when called to scramble they were unable to raise a standby aircraft and crew within the required time scale. The first time was to hold immediate readiness for four fighter aircraft, which were on local sorties and were unable to land because of the sudden advection of fog over Port Stanley airfield. The second was for the Flight's own MRR helicopter, which had an auxiliary hydraulic failure and had landed on an inaccessible part of the southern shore of Berkeley Sound. Nevertheless, the highest priority remained on maintaining the Flight's Search and Rescue role and several rescues were completed successfully. By the beginning of March 1984, the backlog in servicing schedules had been cleared and the Flight returned to its full operating strength. By then the high priority given to the support of the radar stations was also coming to an end and the Flight returned to a more normal rate of tasking.

C Flight 22 squadron had been deployed as a unit to the Falkland Islands. However in November 1983, the Flight was re-named 1564 Flight (the same Flight number that D Flight 22 Squadron had taken on arrival at El Adem in March 1969). The renaming of the Flight was initially resisted by its crews who wished to remain loyal to and under the protection of 202 Squadron, HQ SAR Wing and HQ 18 Group who understood SAR helicopter operations, rather than Support helicopter operations with a SAR commitment. The Flight nevertheless bowed to the inevitable and remained as "1564 Flight (son of C Flight 202 Squadron)" as a directly administered overseas unit in Strike Command. 1564 Flight moved to Mount Pleasant Airfield in April 1986 and in May 1986 it was joined by 1310 Flight (previously the 18 Squadron Chinook detachment at Kelly's Garden) to reform 78 Squadron at Mount Pleasant Airfield (MPA).

The Sea King Flight of 78 Squadron remains at MPA. Its crews are detached from 202 Squadron and C Flight 22 Squadron on a rotating basis (Mk 3A crews, other than Winchmen, are not detached to 78 Squadron as the time and cost of re-training was considered not to be effective). The length of individual detachments has varied over the years from four months during the first few years, to two months for the majority of the time and in late 2000 the detachments were reduced to six weeks. In any event the total length of time an individual could expect to spend in the South Atlantic each tour has varied little since the original detachments. The original Grey Whales were also replaced on rotation with other Mk 3 Sea Kings painted grey and modified before departure from the UK. This had the effect that a mixed colour fleet was operated in the UK. In 1999 it was decided that the 78 Squadron Sea Kings no longer needed to be painted grey; by now all RAF Sea Kings had a majority of the modifications originally needed for Falkland Island operations and, on rotation, the grey Sea Kings were replaced by yellow aircraft. The Grey paint was replaced by yellow when the aircraft were due for repainting.

The very nature of SAR helicopter operations brings its own inherent hazards in addition to those normally associated with military aviation. The aircraft are required to hover for long periods of time, often in the "avoid curve" with no immediate safe landing area in the event of and engine or other catastrophic failure. The aircraft have to be hovered in close proximity to obstructions in order to carry the winchman to the survivor. The aircraft have to be operated in extreme weather conditions and at night to reach survivors and transport them to safety. The aircraft may have to operate at the very edge of their range, endurance and flight envelope to achieve their role. The winchman is required to place his life at risk to enter the environment of the survivor before he can effect a rescue. There have been several accidents involving RAF SAR helicopters and their crews, fortunately in the majority of cases without injury to the crew or passengers. Sadly however, there have been a few fatal accidents to RAF SAR helicopter crews and their passengers, both in the UK and overseas. It is neither possible, nor appropriate, to recount all the accidents. Those lost on SAR duties are remembered by their families, friends and colleagues.